Bodies in Alignment

An eclipse in the life of a family

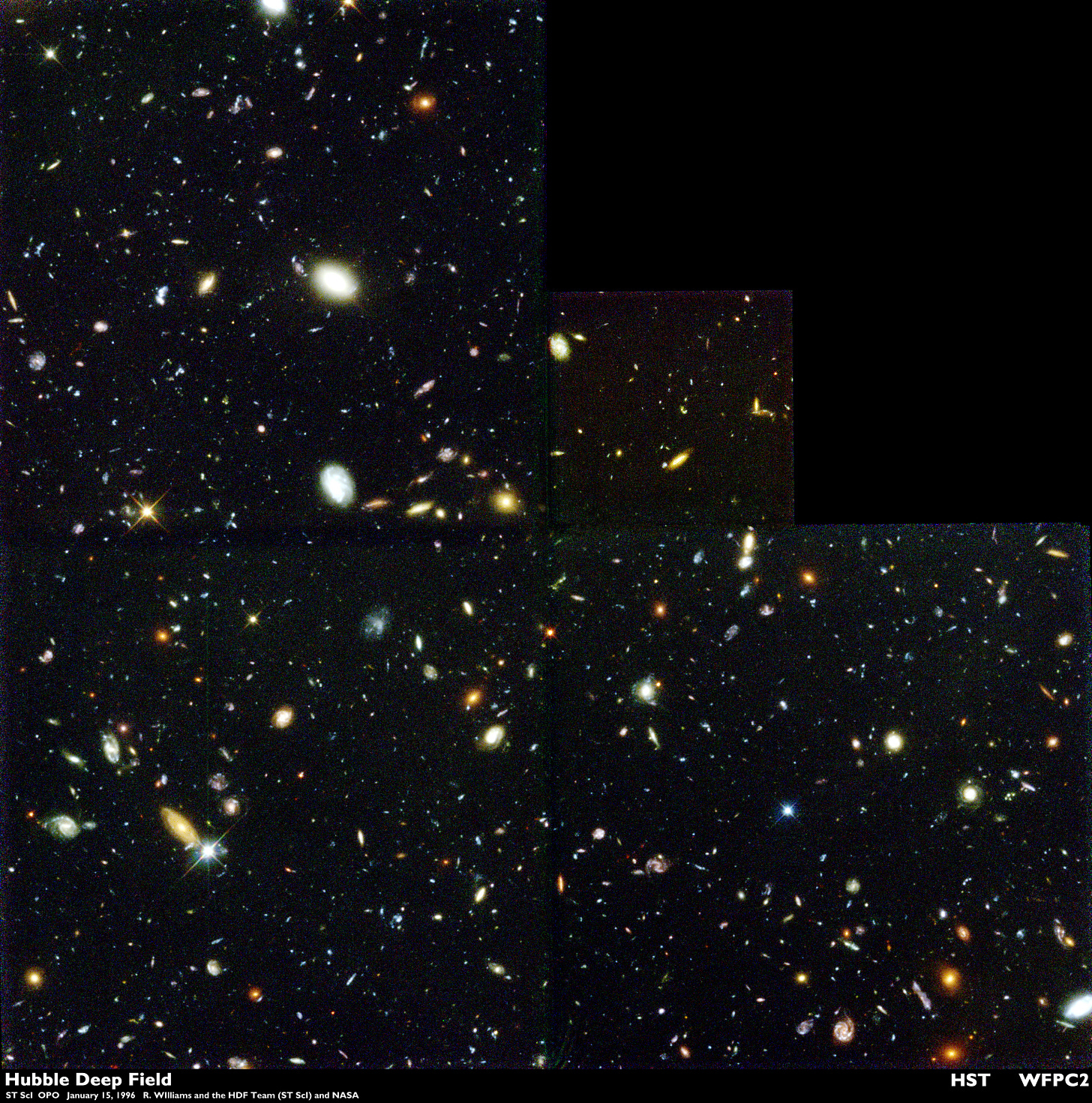

In 1995, Robert Williams directed the Hubble space telescope to make a very expensive gamble. Rather than pointing the lens at something, he spent day ten days pointing it at nothing, at a patch of sky that appeared blank. The nothing, once resolved into an image, turned out to quite a lot of something: three thousand points of light, most of them representing entire galaxies, each containing tens of millions of stars. In our universe, magnificence is everywhere.

It’s true on Earth, too. The stripe of North America covered by yesterday’s solar eclipse passed through cities and towns, and it also passed through a lot of empty spaces where maps mark few spaces of interest. This is how my family came to view the eclipse from a point on the map called “Moosehead” that turned out to be a river crossing just north of Greenville, Maine (population 1,437).

Getting to Moosehead from Philadelphia took some doing: long hours of driving, transferring children from car seats to hotel beds in the dead of night, bored moments and slap-happy games of “Would You Rather?”, rushed breakfasts and gift shops with overpriced maple syrup, white-capped waves on the Atlantic and the jungle gyms a block away, sitting in bed watching Timothée Chalamet sing beautifully forgettable show tunes in Wonka long past everyone’s bed time. The eclipse itself was barely two hundred seconds, and the traffic on the back end was awful. Who would do this for anything less?

Total eclipses don't photograph well with normal cameras and the “good” pictures end up looking much the same, displaying the spectacle in all in its glory at the expense of all the context (the trees, the snow, the people) that made it feel worth beholding. Like many of life's most important events, all you can take away with you are memories.

Eclipses are not inevitable. They are one of Earth’s many celestial curiosities; another is the presence of life, the presence of an America with rivers that rush past snow-covered woods, the presence of people who love us. The camera that we brought to film the eclipse died five minutes before totality, and without a telephoto lens even the captured footage is unimpressive. So much for the video. What the camera did capture—accidentally—was fifty-five minutes of the sounds of our family, six bodies in alignment with one another for this brief moment in each of our lives. That this audio track is accompanied by grainy images of a crescent sun will be, those who watch it, only secondary. Either way, both testify to a single glorious miracle: the wild chance that every once in a while, through actions only partially our own, life comes together.