How Jews and the Amish Accidentally Invented the Same Lamp

The two communities develop tech the same way for the same reason.

For many years I’ve had an intense fascination with Amish technology. If “Amish technology” seems like an oxymoron, I want you to look at the picture below.

What you’re looking is a piece of modern Amish technology. Specifically, this is a normal wall-mounted light fixture that has been modified so that it can run on an 18-volt power tool battery. This has been done because Amish communities are not typically anti-electricity per se, but they are frequently against electrical grids, which create both literal and symbolic connections to the outside world. (The batteries themselves are charged with solar panels or generators.)

If you’re not Amish, this device may look exceedingly silly: after all, it’s just a lamp that’s slightly more annoying to use, and it is no less a product of American technological advances then the grid itself. What hypocrisy!

If you’re a Jew who observes the laws of Shabbat, however, this object may look oddly familiar. This is because Jews have light fixtures designed to do something very similar.

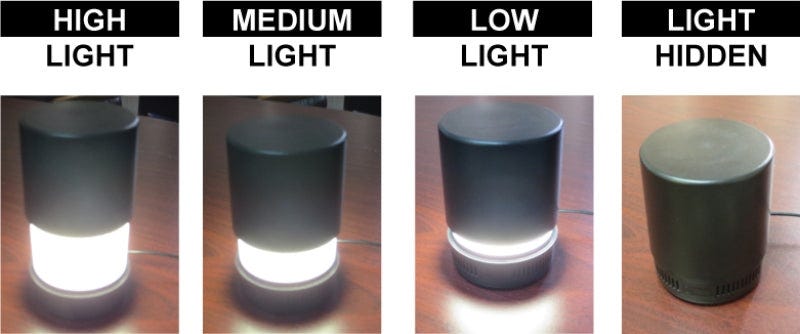

This is a piece of modern Jewish technology. Specifically, this is a device called a Shabbos lamp. It’s a normal table lamp, but it has been fitted inside a special enclosure so that you can block out all of its light without actually turning it off. This has been done because Shabbat-observant Jews are not against electricity on Shabbat per se—you can use all the electrical lighting you want—but they are against the active manipulation of electricity. This device allows the user to “turn on” and “turn off” the light without formally breaking the laws of Shabbat.

In other words, both Jews and Amish communities have responded to their communities’ rules around electricity by creating entirely new devices designed to conform to the religious regulations while retaining all of the functionality of ordinary light sources. Rather than change or ignore the rules, they engineered their way around them. (Incidentally, both device are only possible because of the transition to LEDs. Incandescent bulbs don’t last long on batteries, and they’d melt any plastic housing.)

And it’s not just lights. In the last few decades both Amish and Jewish communities have invented dozens of devices that incorporate religious requirements into their design. Jews have the Shabbat elevator and the kosher switch; the Amish have the high-tech buggy and the pneumatic ceiling fan. (For an extensive treatment of Amish technology, Lindsay Ems’ recent book is excellent. For a list of similar Jewish devices, take a look at the Tzomet Institute.)

Outsiders may look at these devices and protest that they are dumb workarounds that violate the spirit of the law. But both Shabbos and Amish lamps are popular, and the people who buy them are not at the fringes of their communities. Instead, something much more interesting is going on here, and it’s something that I find encouraging for thinking about the future of technology.

Tech adoption isn’t a binary

When a new technology becomes available to the public, it’s easy to imagine that it’s presenting a choice: use me, or don’t. This choice often doesn’t feel like much of a choice at all, because people frequently feel that the way they use tech in their lives is really dictated by work other people expect them to use. Most people just wait and see what becomes standard.

But this isn’t really how it works, or at least it doesn’t need to be. Engagement with technology isn’t a binary choice between full embrace and absolute rejection, and full embrace doesn’t mean that the end user has no say in how the technology will be used. As historians of technology have been saying for decades, technology doesn’t just dictate to people how it is to be used. Instead, all technologies—especially the world-changing ones—exist in constant relationship to communities of human users. Those users exert a huge influence on the way that the tech appears in the world, to the point that the distinction between inventor and user can get blurry.

This comes out very clearly in both the Amish and Jew light fixtures. Both are attempts to create some distance from electricity—either in specific settings or at specific times—out of concern that it will disturb a well-constructed way of living. Rather than simply say no to electricity, however, both communities have responded to electrical devices by making electrical devices of their own, using creative design to extract the benefit of electric lighting while preserving the desired atmosphere. Instead of distancing themselves from the culture of invention, both communities have fully embraced it (at least in this instance).

What does a “religious response” to technology look like?

I am inspired by these responses because they represent religious communities taking charge in a situation where they could have easily fallen into passive acceptance or rejection. No lighting manufacturer invited Jews to invent the kosher lamp (years ago I asked the inventor, so this isn’t just a guess!) Such things are created by people who understand that the best response to innovation is more innovation. This is especially true when you’re facing innovations that scare or overwhelm you. There’s never a moment when innovation stops being the right choice, because in a complex world it’s the best way to optimize for the things you want.

To go back to the idea of a previous post, it’s easiest to respond to technology with creativity when you’re clear about what really matters to you. The Amish know that they care about being disconnected. The Jews know that they want Shabbat to feel distinct from other days, and they know that manipulating electricity takes people out of the Shabbat experience. Both communities understand that making a device slightly annoying to use (Ems calls these “speed bumps”) can also make one think about it as a carrier of values and not just a utilitarian object.

Lighting companies don’t think about Jewish or Amish values when designing their products, but that doesn’t mean Jewish and Amish values can’t be embedded in a design. Religious communities can use innovation, in both software and hardware, to encode their values in technology. It just takes a little creative thought.

Rabbi Shai Held once quoted his son (the younger, IIRC) as saying "We shouldn't make fun of the Amish, we spend one day a week trying to live like they do."

A very thoughtful article.