Why Abraham Joshua Heschel Criticized the Moon Landing

Religious leaders were important critics of the space program. Why did they stop?

54 years ago today, humans landed on the moon for the very first time. Four days prior, Ralph Abernathy arrived at the launch site, a few mules and dozens of people in tow. Abernathy, a Baptist minister, was Martin Luther King Jr.’s successor as head of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference. He had arrived to protest.

It was not Apollo 11 that he was protesting, Abernathy was careful to say. Rather, the country needed to reckon with its “distorted sense of national priorities.” At a time when more than 2% of all federal spending was going to NASA, there was “an inexcusable gulf between America’s technological abilities and our social injustice.”

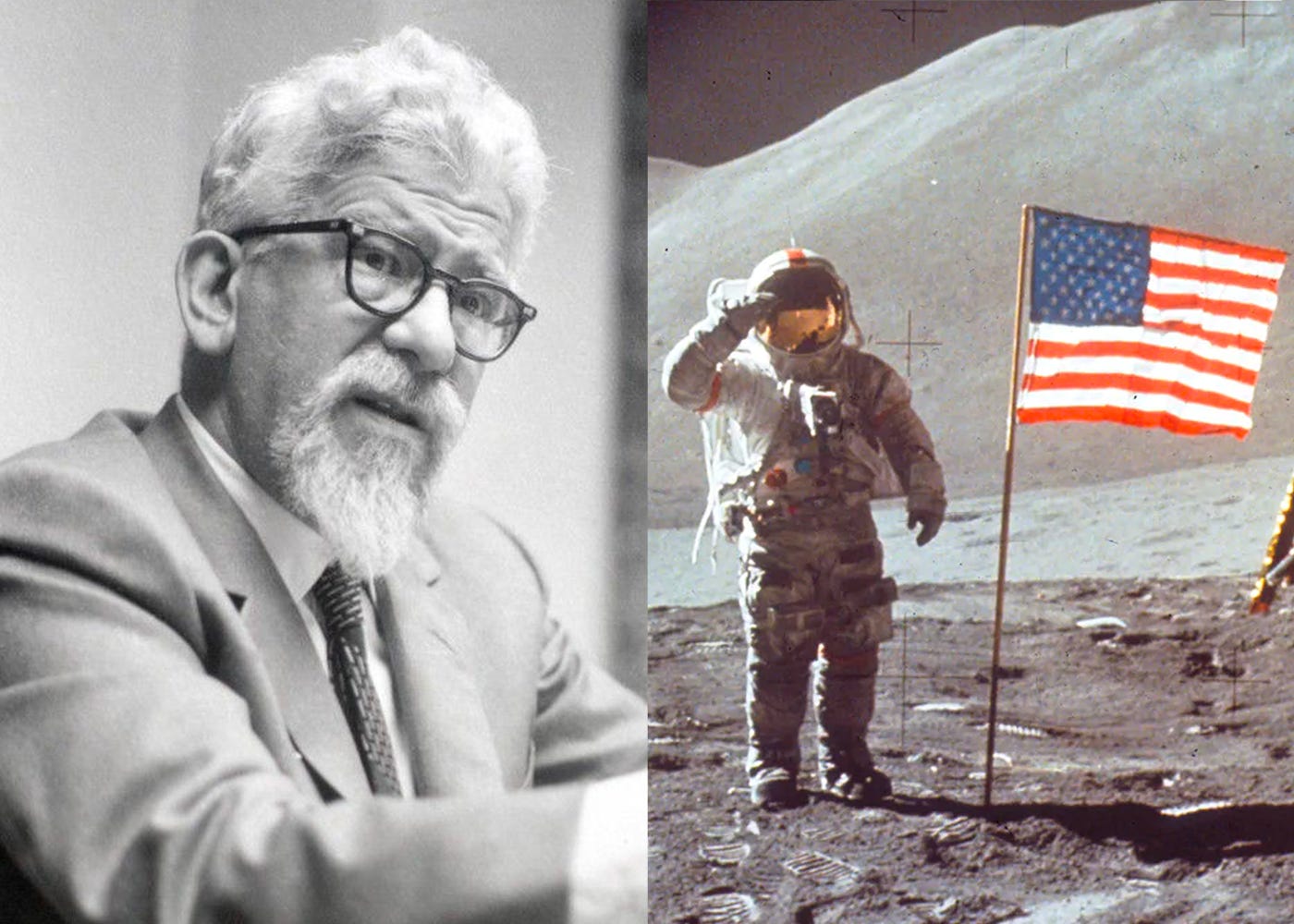

Abernathy wasn’t alone. In a 1964 essay titled “The Moral Dilemma of the Space Age,” Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel suggested that the government’s grand rhetoric about humanity reaching the stars might just be a smokescreen for political and military goals.

Is the discovery of some form of life on Mars or Venus or man’s conquest of the moon really as important to humanity as the conquest of poverty, disease, prejudice, and superstition? Of what value will it be to land a few men on the wilderness of the moon if we neglect the needs of millions of men on earth? […]

It is our duty to point out that in placing lunar exploration above more fundamental human values there is a loss of self-respect, a sort of cheapening of human life. While there is no theological prohibition against doing research beyond the confines of this planet, what is really involved is the matter of doing the right thing at the right time. In my judgment, this is not the right time to invest more than $5 billion annually in space, measured against the less than half a billion we are allotting over a four-year period for the retraining of men and women whose productive capacities have been made obsolete by a mushrooming technology, or the less than $1 billion that President Johnson has recommended to fight the poverty that keeps more than one-fourth of our nation ill clothed, ill housed, and ill fed.

Heschel was right to be concerned. Coverage of the civil rights movements regularly conflicted with updates from NASA. News coverage of the third Selma march, in which King linked arms with Heschel and other religious leaders, was abruptly cut short to broadcast a press conference about the Gemini 3 space program.

It seems strange today that religious leaders would be so invested in space travel, but this probably says more about us than them. At its height, space was everybody’s business, and for many people it was a religious idea. Soaring through space evoked religious sentiments in NASA personnel and the public alike. The theologian Paul Tillich reread Psalms in light of human ambition. Wernher von Braun, the Nazi scientist turned NASA architect, saw rocketry through an evangelical Christian lens. John Glenn prayed in space, and Buzz Aldrin took communion on the Moon. Zalman Schachter-Shalomi, leader of the Jewish Renewal movement, thought that the sight of Earth from orbit was a historic call to action.

But at some point religious excursions into space stopped cold. Mention space in a sermon today and your congregants might think you're from space. Space travel has continued to improve, especially in the private sector, but discussions about it are now the domain of select groups: enthusiasts, tech journalists, the federal government—and, of course, billionaires like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos who build rockets and talk about traveling to Mars and beyond.

According to the religious scholar Mary-Jane Rubenstein, this is a problem. The idea of humans traveling to the stars is always going to invoke religious sentiments, but today those ideas are deployed in service of some alarming philosophies that bear little resemblance to what modern (Christian) theologians believe. Making things worse, these ideas share some eery similarities with long-renounced church-backed ideologies that provided cover for violent acts against both human beings and the environment. In her book Astrotopia, Rubenstein argues that it’s time for religious thinkers to reenter the space conversation so that we don’t repeat the mistakes of Earth’s past in our spacefaring future.

Space isn’t Special

The roots of Astrotopia extend back to the start of the environmental movement more than fifty years ago. In a landmark 1967 essay, the historian Lynn White, Jr., argued that ecological destruction was partially the fault of a Christian interpretation of the biblical Creation story in which God commands humanity to be stewards of the planet, ranking them higher than everything else in the cosmos. This created a dangerous hierarchy in which human desires always trumps everything else, where stewardship decays into blunt dominion, and where all of nature exists at the pleasure of humanity.

But it gets worse, because the people who presume to speak on behalf of humanity never actually do; it’s a rhetorical strategy, and it’s designed to project power. Rubenstein documents how the same ideology of divinely-sanctioned dominion that was trotted out time and again to justify European colonial “ownership” of New World soil and the deaths of countless indigenous people found new purchase in America during the space race against the Soviets. These grand stories of destiny—God not only allows but wants people to conquer America, wants Americans to land on the moon—are powerful distractions from what are often very particular capitalistic or political interests. As Rubenstein writes: “Just as God had called the Israelites into Canaan, the Europeans into Connecticut, and the Homesteaders out to Colorado, so was [America] now—in the face of its Soviet rival—calling America to the Moon.” Yes, the moon bears a plaque from Apollo 11 states We came in peace for all mankind—but that plaque sits next to a firmly planted American flag.

The privatization of the space industry makes this problem even more extreme. If the American government can’t speak for humanity, then a billionaire certainly cannot. This hasn’t stopped Elon Musk from insisting that “we must preserve the light of consciousness by becoming a spacefaring civilization [and] extending life to other planets,” nor has it stopped Jeff Bezos from framing Blue Origin as civilization’s salvation. Rubenstein compares these rhetorical moves to the pesticide industry’s response to Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring: the ecological damage is justified because we are feeding the world. Similarly, NASA tried to claim that it really was fighting poverty because its fuel cells could be redesigned to purify drinking water. They never were.

An easy criticism of Rubenstein’s argument is that colonial conquests had sentient life in them, while space, as far as we know, does not. Why not claim ownership of an asteroid? It’s not like anyone else is using it. But Rubenstein notes that this argument is just an extension of a bad colonial habit to treat human improvement as a mark of value. Some people have sacred temples and others have sacred mountains, but we’re pretty good at respecting the former and tend to ignore the latter. It’s almost too perfect that Mauna Kea, a mountain considered sacred by native Hawaiians, has been home to a major observatory since the 1960s, despite repeated protests.

Like Abernathy and Heschel, Rubenstein doesn’t think the grand space narrative is nonsense. There really is something breathtaking about journeying to other worlds. But the space narrative is intoxicating, and it is designed to make other human narratives feel small. We can understand why millions of people watched Neil Armstrong step onto the lunar surface with a sense of awe—but we should also understand why 50,000 people at New York’s Harlem Culture Festival who greeted news of the momentous occasion with a round of boos.

Rubenstein doesn’t really help balance these two impulses; at the end of the day, Astrotopia takes ideas apart better than its puts them back together. She succeeds at her goal of piercing modern space travel’s civilizational rhetoric, and it is useful to label and criticize the use of outdated and dangerous Christian theologies. But the landscape of space travel has changed, and it’s a lot easier to tell a government what to prioritize than it is to tell a billionaire how to spend his money. As with religious environmental thought, new theologies don’t necessarily lead to new policies. Still, space is big, and our explorations have only begun. Someone needs to balance the rhetoric of humanity’s celestial destiny against the need to treat actual humans with dignity and respect. This was once a project for religious leaders. Rubenstein suggests that the time has come again.

Two questions:

1. No doubt some advised Ferdinand and Isabella not to subsidize Columbus’s voyages to the west. To them, and to Heschel and Abernathy, if not then, when?

2. Given that some “religious leaders” cannot distinguish between global warming and climate change or even correctly state when human life begins, why would you think that on a matter involving science and communal well-being, they would have any unique insights in support of “balance,” or even any wiser thoughts than historians, economists, sociologists, humanists, or ordinary blokes, among others?

Excellent article.