The sad man on the Manischewitz box

A foreshadowing of things to come

Here’s something short but sweet(?) about America’s favorite Jewish manufacturer: Manischewitz. This post is perhaps more trivial than most, but I hope it gives you something to think about the next time you’re out shopping or sitting at the seder table.

It’s about Passover—but really it’s about AI.

Manischewitz did a great rebrand with one error

Last year, the venerable Manischewitz company underwent a major rebrand under new ownership. The company leaned into its famous shade of orange, and brought in illustrator Maria Milenko to bless every product with artwork that evokes (what else?) New Yorker cartoons. If you’ve been shopping recently you might have seem the artful containers of gefilte fish, potato knishes, grape seed oil, and egg noodles.

The rebrand is good. Milenko’s artwork is fun and distinctive—with one major exception.

There is something seriously wrong with the artwork on the box of matzah.

A happy man shoveling matzah into an oven. Cute, right? No, it is not cute. It is incorrect, in a way that would make the founder of Manischewitz either laugh or blush.

This is because Manischewitz is not and never was a handmade matzah operation. In fact, the person depicted on the carton is exactly the type of matzah-making operation that Manischewitz was built to replace.

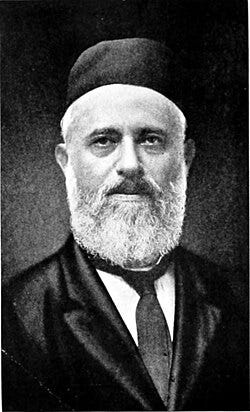

Manischewitz is the avatar of industrial Judaism

“Dov Behr Manischewitz” was the name on the passport of a dead man. The man who bought that passport and assumed his identity—perhaps escaping military conscription in the process—was a Lithuanian Jew with an eye for business.1 In 1886, he arrived in Cincinnati; two years later, he founded the Manischewitz matzah company right at the onset of industrial food manufacture. By 1900 this not-so-humble matzah maker (he was a butcher by training) had scaled his operation into a massive enterprise. Dov Behr wasn’t just riding the coattails of other industrialists; he was leading the charge. Search the US Patent Office and you’ll find many patents issued to the Manischewitz company for innovative new ways of process matzah at unheard-of speeds. Dov Behr was to matzah what Sefaria is to Jewish learning: cutting-edge tools to serve an age-old need.

The problem was that industrial food plants didn’t have a sterling reputation. Consumers didn’t know who was making their food and they had no assurances that it was safe to consume. These concerns ultimately led to the creation of the FDA, but matzah makers had the additional problem that they needed to assure the public that their food was kosher for Passover, which is a notoriously high standard. Kosher certification agencies wouldn’t exist for another 25 years. Jews did not have any standard means of verifying the suitability of food that wasn’t made locally.

Dov Behr solved this problem by being radically open. Any rabbi, he advertised, was welcome to inspect his factory at any time. Many rabbis did. Eventually they were convinced, and so was the American public.2 The industrial matzah won, Manischewitz exploded in popularity, and America has never looked back.

The man on the box was competing with Manischewitz

As in many other sectors, the industrialization of matzah put most hand-made matzah producers out of business. Whereas matzah had previously been produced as a sort of fundraiser for the needy (not unlike Girl Scout cookies), most Americans now got their matzah in little square boxes from the grocery store.

This isn’t inherently problematic, but it makes the illustration on the matzah box very strange. It’s fine to romanticize an era when men slid matzah into an oven like personal pizzas—but it’s a little strange when the people celebrating are the ones who brought that era to a close. I get that the image is a lot friendlier than a doodle of a man in a hairnet observing a production line, but the result is just historically absurd. The box designers might have thought they were reminiscing about their company’s origins. Instead they managed to turn the matzah box into a cardboard epitaph.

It’s a metaphor about AI

Yes, I know that the design of a cardboard box is a pretty low-stakes worry. Manischewitz isn’t trying to trick anybody, and I’m sure this design was created in good faith.

So why do I care about it? Mostly because it feels like the epilogue to a story that, in a totally different part of the economy, is only now beginning.

A couple of years ago I wrote about how matzah is the perfect metaphor for AI in the labor market. Before the middle of the nineteenth century all matzah was made by hand; Jews had been doing it that way (supposedly) since leaving Egypt. Then industrialization came and rabbis briefly battled over whether its benefits (faster production, cheaper matzah) outweighed its problems (people losing jobs, new quality control issues). The machines won—and within a few decades the win was so decisive that human-made matzah became a luxury good (the 3 lbs. I bought this year cost a whopping $92). Today the idea that a normal human could make matzah—a product which exists because it is simpler to make than even bread—is almost inconceivable to most Jews. Despite being the least “processed” food imaginable the product is now permanently in the realm of the machines, and it is never going to leave. When the machines win, they win for good.

Manischewitz wasn’t trying to kick hand-made matzah out of the matzah market; it was just trying to make food quickly and cheaply, and it did that extremely well—so well, in fact, that people forgot things had ever been any other way.

When you look at the Manischewitz matzah box you’re supposed to think about the company’s humble roots. If Google started with a garage, says the matzah man, then why can’t I start with a simple brick oven? But Manischewitz doesn’t do “quaint,” just like gasoline doesn’t doesn’t do “calm mood lighting.” Manischewitz was built for speed, not sentimentality—and because the price was right we decided to go along. Thousands of years after the Exodus, the Jewish people decided to alienate themselves from the means of producing their own Bread of Affliction. All we have left are the stories—or in this case, a whimsical cartoon.

Think about the tasks we hand over to AI today. In a century, will we even believe that human beings could do those things? Will we be too wealthy to care—or will we feel that something has been lost?

I have seen several versions of this origin story for the Manischewitz name (including Gil Marks, the late historian of Jewish foods), but to be fully transparent I cannot determine their veracity.

For these and many more details, take a look at Jonathan Sarna’s article. The definitive article on machine-made matzah is unfortunately paywalled, but you can find many summaries online.

counterpoint: maybe he's happy that he doesn't have to do the backbreaking work of making matzo by hand! Levi Yitzchok of Berdichev said about the process of making handmade matzo, “Those who hate Israel accuse us of baking the unleavened bread with the blood of Christians. But no, we bake them with the blood of Jews!”

Really interesting! Another angle to the Manischewitz matzah origin story -- according to some pop historians (I've tried but haven't been able to corroborate), Manischewitz matzah was actually purchased by pioneers making the westward trek in the late 1800s; it was a good shelf-stable alternative to bread (and tastier than hard tack, I guess). I shared this historically suspect fun fact with my 7th grad social studies students (Jewish day school, thus the hook!) during our westward expansion unit. On second thought, maybe I shouldn't be surfacing the connection between matzoh and western colonialism :-)