The Dreidel of the Future: From Pretty Prototypes to Hardware Hell

Dreidex v0.1 and v0.2

They say that God made and destroyed ten thousand worlds before creating our universe.

That’s what building the Dreidex has felt like. Only more so.

(This is part of a series on creating the world’s first hackable electronic dreidel. You may want to read part one to understand how I got here.)

Hardware is hard

I know a little about electronics, but not that much. I can solder an FM radio if you give me all the components, and I could probably explain what each of them do—but I couldn’t design a radio, let alone create a custom circuit board for manufacture.

Still, it was clear to me that the dreidel of the future was going to be a persistence-of-vision (POV) fidget. I knew that I needed help, so I started working with a hardware designer in India.

The basic design was clear from the many hobby devices that have appeared since 2017, but I wanted to make my dreidel a little slicker and a little more capable. For the first prototype, we made two small changes:

We added a programmable function button toallow the user to switch between diaspora mode (נ–ג–ה–ש) and Israeli mode (נ–ג–ה–פ).1

Most consequentially, we decided that the device should run on rechargeable lithium coin-cell batteries. Because most people don’t have a recharger for coin cell batteries, this meant we needed to built charging circuitry into the device itself.

The second change turned out be massively consequential.

In order to charge the batteries, we needed a way to feed it AC power. The easiest way to do this was to add a USB-C port. Easy enough.

But that USB-C port tempted us to do more. It was there to supply power…but couldn’t it easily supply data, too? Well, yes!

Just like that, the idea of a programmable digital dreidel was born. We’d have the device ship with factory-installed dreidel software (which is a very strange sentence to say out loud), but we’d give the user the ability to turn the device into anything they wanted.

In order to make this process easy, we settled on the ATmega328 as our microcontroller. This is the same processor used in the extremely popular Arduino Uno, which is commonly used in all sorts of small hardware projects (sensors, small robots, kinetic art sculptures). It is very well understood. As a bonus, it can be programmed with the well-documented Arduino software toolkit, which massively simplified development.

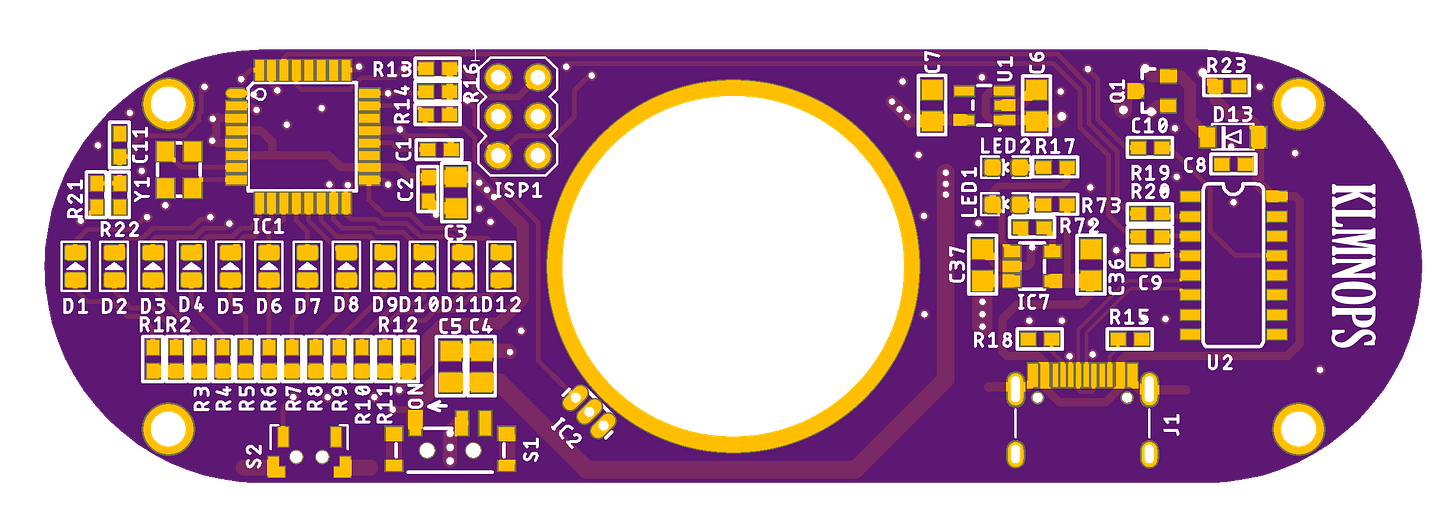

This ultimately led to a prototype board that looked like this:

The design went to EasyEDA, a circuit board prototype manufacturer.

The prototypes came back. We noticed a mistake and revised. More prototypes came back.

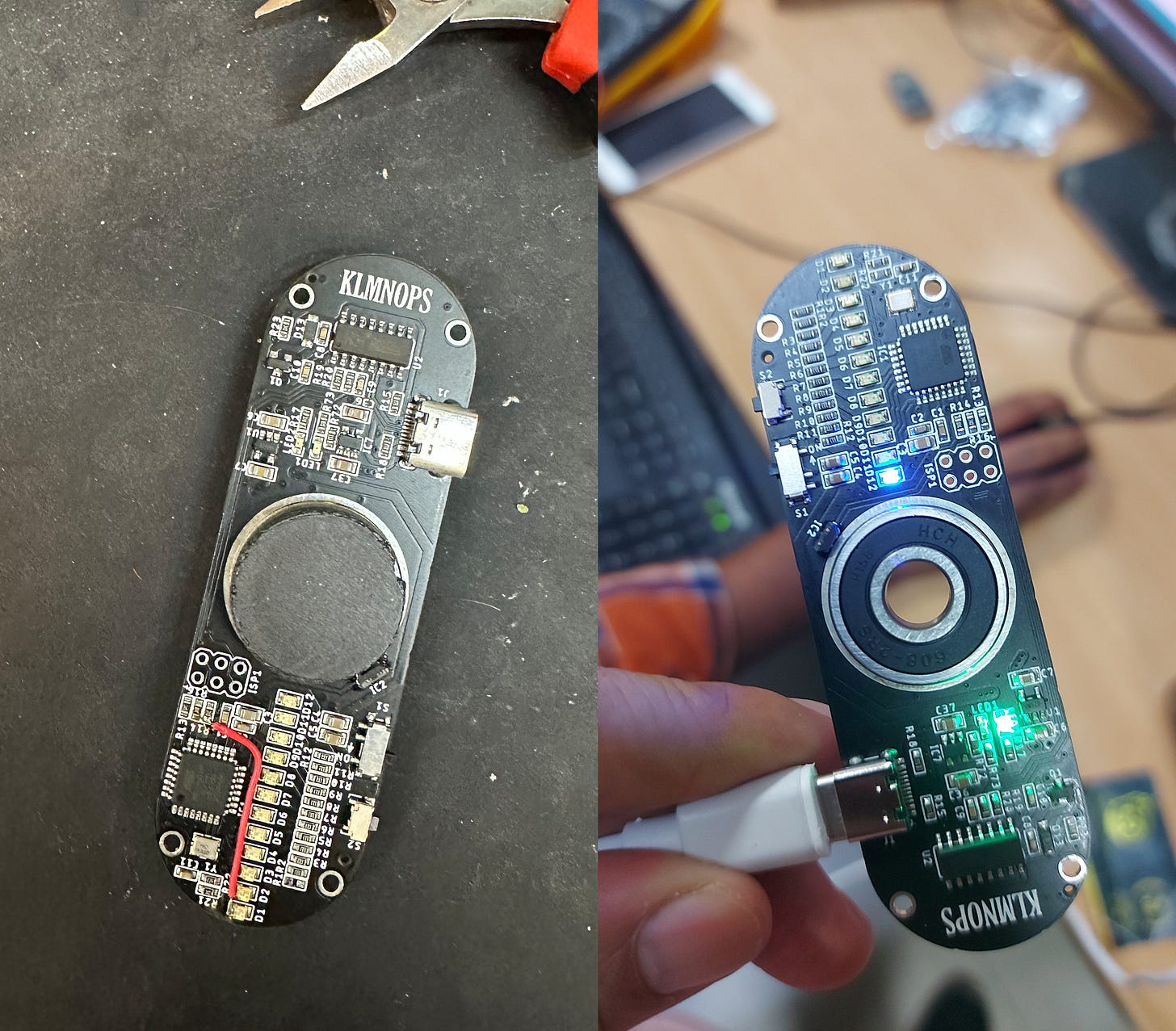

And this is them—Dreidex v0.1 and v0.2!

Many times in my life I’ve had the experience of holding a book that I’ve worked on for the very first time. This was like that—but this thing had batteries and cool little lights!

Both devices worked, but both had problems.

First, it turns out that fidget spinners don’t use regular ball bearings. Most bearings have internal lubrication to reduce noise and vibration and to prevent the metal parts from grinding themselves to death. The problem is that lubrication also increases friction, which means the devices couldn’t spin for more than 10 seconds at a time. My designer needed to go out and find fidget ball bearings, which are open and allowed the device to spin for at least 30 seconds with a casual flick.

Finally, we got to the point where the device could display text.

(Unfortunately, footage of POV fidgets don’t film great because the phone’s frame rate doesn’t mimic the way it appears to the human eye. Trust me that it looks better in person!)

You can’t just ship a dreidel circuit board

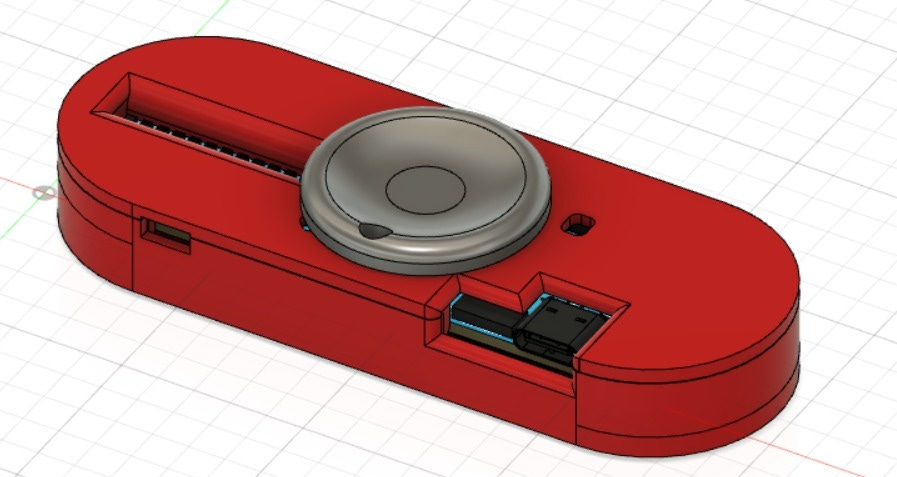

This was an encouraging sign, but major obstacles remained. Most importantly, the device needed a case.

This proved to be quite difficult because the case is actually essential to a POV fidget’s operations. In order to display text that appears to hang in the air, the fidget needs to know how fast it’s spinning and adjust its display frequency dynamically; otherwise, the text will contract as the fidget slows down, as you can see below.

There aren’t a lot of ways to do this well. You might think that the obvious choice is to give the fidget a gyroscope (like the phone in your phone), but cheap and tiny gyroscopes aren’t designed work on devices that are spinning at 1,000–3,000 RPM.

Instead, almost everyone who has made a POV fidget has used a Hall effect sensor, which senses magnetic fields. The sensor is mounted on the board very close to the bearing (in the photos above it’s labelled IC2). A small magnet is then embedded in a plastic cap that you hold while spinning the device. The board rotates; the cap doesn’t. By measuring how quickly one passes the other, you can determine the rotational velocity and create graphics that appear to be hanging in the air.

In short, you end up with something like this.

In theory, this should have worked like a charm. In practice, however, it turns out that Hall effect sensors are kind of finicky, which meant that small imperfections in the case could made the device stop functioning.

Worse, the case was big. An adult could comfortably hold this dreidel between thumb and forefinger, but a kid couldn’t, and the case only made the device chunkier. Fidgets are supposed to have style, and this fidget just didn’t feel sleek. The idea was cool, but when I showed the device to people they didn’t seem all that impressed. Something was off.

The dreidel winter

And then…I stopped working on the project.

Everything that I’ve described up until this point happened back in 2020–2021. I had built two prototypes and the device, if carefully coaxed, could do something interesting. But I was still far away from a functional product, or even something I could share for preorder purposes. It just didn’t seem that impressive.

Worse—I was worried about losing the idea. I’ve heard too many horror stories about intellectual property getting stolen when people announce their products too early. Someone in the dice manufacturing world even told me that a product was copied and shipped using the promotional images he had created for his Kickstarter.

So the product was in limbo—cool enough to fantasize about, but not advanced enough to tell anyone about. I’d carry a prototype around in my backpack and tell people about it when the moment felt right; it was a kind of totem of a product that could be, or maybe of my aspirations to be a hardware manufacturer. But Hanukkah after Hanukkah ticked by, and the device was no closer to being in the world.

And then—this year—I had a breakthrough. Actually, two breakthroughs.

This story is continued below.

Dreidels originally had the letters נ–ג–ה–ש, the first letters of Yiddish words explaining the actions to be taken when the dreidel fell on that letter. These letters were retroactively interpreted to mean nes gadol hayah sham, “a great miracle happened there [Seleucid-controlled Judea].” On the basis of this back-formation, Israelis started minting dreidels with נ–ג–ה–פ = nes gadol hayah poh, “a great miracle happened here.”